Plant-based food manufacturers often talk about price and taste parity as the biggest obstacles to enjoying mainstream acceptance. But a recent panel discussion at Food Frontier’s inaugural conference, AltProteins22, proved it’s far more complicated than that.

The discussion analysed a number of barriers that manufacturers typically face when promoting plant-based food products, and one overarching theme became clear: perception is reality. A consumer’s initial thoughts about a product – be they accurate or not – have a huge impact on their purchasing decisions. And for plant-based brands, the biggest issues revolve around access, processing and health.

Trial is key

As a food manufacturer, getting your product on supermarket shelves is one thing, but getting consumers to actually pick it up and give it a go is another.

This is where the foodservice sector plays a key role.

A growing number of plant-based meat manufacturers are partnering with foodservice operators – particularly in the QSR market – with the hope that consumers will try their product, enjoy it, then buy it again, or grab it from their local supermarket and cook it themselves at home.

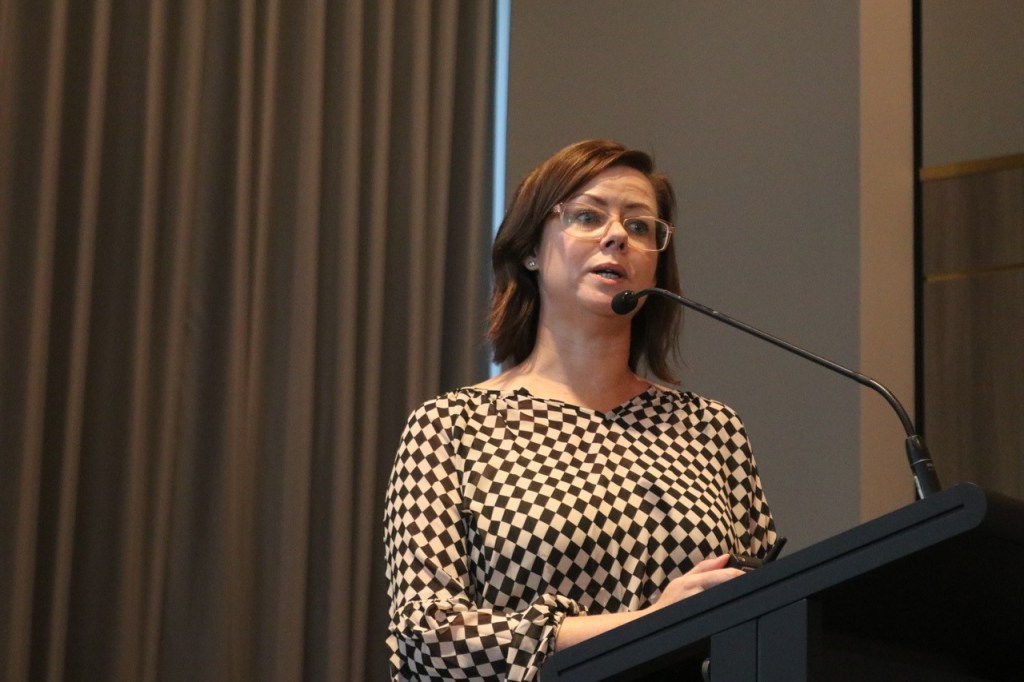

Leaving the cooking to professionals means consumers are more likely to have a great first experience when sampling plant-based products, said Sinead Golley, behavioural scientist at the CSIRO.

“It might also have the potential to [help] overcome some of those concerns we’ve seen mentioned by consumers. That is, I don’t know how to use this? What about the texture? How do I cook it and what do I eat it with?” she said.

Tony Green, CEO of the Australian Foodservice Advocacy Body, agreed that partnering with foodservice is all about low risk trial. Minimising risk is also why most plant-based meat manufacturers first go the market with familiar food formats, like burger patties.

“If you think about foodservice and the top 10 dishes that people go out and eat, the burger is one of them,” Green said. “I think volume and more engagement will come as more of those top 10 dishes get replicated … For example, schnitzels are coming out; they’re another top 10 dish.”

While foodservice is often an effective launchpad for new plant-based products, they first need to win over the ones tossing pans or writing menus.

“You’ve got an extra layer of gatekeeper when it comes to foodservice,” Green said. “You’ve got to have a chef that believes the product is worth putting on the menu.

“The constant comment I hear from chefs is ‘What is it? What’s in it?’ I know there’s a lot of protection and IP around process in this industry, but what’s the sort of generic process that we can share with chefs to take away some of the stigma of, ‘what the hell is it?’”

What is natural?

This wariness of plant-based product is a problem that’s not exclusive to the foodservice market.

“There seems to be a lot of consumer concern around the intrinsic components of these products,” Golley said.

“So, how much processing is involved? Are there additives added to make it perform and look like it does? … We know that at a subconscious level, consumers are not associating plant-based protein as ‘natural’. They see animal-based protein as more natural at this point and even when we’re looking at some of the negative attributes, plant-based protein and animal-based protein are head-to-head when it comes to words like ‘unappealing’ or ‘toxic.’”

Teri Lichtenstein, accredited practicing dietician and nutrition marketing consultant, agrees that – for better or worse – ‘natural’ and ‘processing’ are closely related in consumer minds.

“What does natural mean? I bet if I ask every single one of you in this room, we would all have slightly different definitions of ‘natural’. It’s kind of intertwined with the whole processing topic. But I think ‘processing’ and ‘nutrition’ is not a linear relationship, and we need to disassociate those terms,” she said.

A processed product is not necessarily an unhealthy one, and Lichtenstein insists that more research needs to be done to inform consumers about the long term impacts of eating plant-based products.

“We need to invest in big, long term clinical trials to look at the impact of these more nutritious processed foods on long term health outcomes,” she said. “We need more research and the more we have, the more the media will pick up on it, and the more consumers will realise that even if they don’t define these products as natural, they can actually be healthy for you.”

The health hurdle

Closely associated with the terms ‘processed’ and ‘natural’ is ‘health’, and according to Lichtenstein, it’s not as simple as defining something as healthy or not. For plant-based products, it’s all about being ‘healthier’.

Lichtenstein co-authored Food Frontier’s 2020 report, Plant-Based Meat: A Healthier Alternative? which compared the nutritional profiles of plant-based products with their conventional counterparts.

“We found that on average, plant-based meats were either comparable or superior from a nutritional perspective. So plant-based meats were lower in kilojoules, they were lower in fat, and specifically lower in saturated fat, which we all know we need to be avoiding,” she said.

“And then finally, looking at the Health Star rating, which is the system we have in Australia that consumers can use when choosing within a category, and in five out of six cases these plant-based meat products were superior.”

Having said that, Lichtenstein warns consumers that swapping a traditional animal-based product with a plant-based one wont necessarily deliver the same nutritional outcomes.

“We don’t eat nutrients, we eat food. So you have to consider the whole food matrix,” she said. “When you’re looking at something like a plant-based milk, it might be fortified with the same nutrients you find in dairy milk, but we know that the bioavailability is not necessarily the same.

“It’s an area that we are significantly lacking when it comes to plant-based meat categories. So even if [manufacturers] add iron and B12 and zinc and all those nutrients inherently present in traditional red meat, how much do our bodies absorb?”

Using dairy-free and gluten-free as examples, the CSIRO’s Sinead Golley said that for consumers, it can often be about what they’re avoiding, rather than what they’re getting.

“People aren’t just jumping on the bandwagon because it’s cool to go dairy-free or to say ‘I’m gluten-free’. They’re doing it because they perceive health consequences when they consume those food components. So for example, if you’re looking at alternatives to dairy milk, I think they really benefited from the growth of that association that [dairy] was bad for quite a large proportion of the community. And there were options available that consumers could still enjoy with their coffee and cereal, without having those quite awful side effects,” she said.

At the end of the day, winning over consumers is all about gaining trust. With the plant-based market becoming increasingly competitive, it’s critical that brands making health or sustainability claims actually walk the talk.

“If the benefit of a new product category, new food or new technology is seen to rest solely on the manufacturer or producer and not the community, then they’re going to lose [consumer] trust,” Golley said. “It’s important that your messaging is consistent and delivers on promises. Because you’ll lose consumers if it’s just seen as a money making exercise or an attempt to grab market share.”

To stay up-to-date on the latest industry headlines, sign up to Future Alternative’s enewsletter.

Posted on:

Excellent article with thought provoking suggestions to food alternatives. Most informative.