It didn’t get much attention when US President Joe Biden launched a biomanufacturing initiative last September.

But it should have. Biomanufacturing is about harnessing nature’s factories – cells – to make just about anything. That includes food. As Biden pointed out, biomanufacturing could boost food security at a time when prices are spiking amid geopolitical strife and unprecedented droughts, floods and fires.

How? By cultivating meat. Having a lamb roast for dinner has traditionally required rearing animals, slaughtering them, and discarding inedible parts. But technology has advanced to the point we can now grow animal muscle cells in bioreactors.

To date, Australia has no such initiative. But we should. Agriculture and biotechnology are two of our national strengths. And we are exceptionally vulnerable to climate change. Cultivated meat has come a long way, but it’s still not cost-competitive with traditional meat. The last hurdle to be overcome is scale.

Why do we need this technology?

To create a new farm, you have to remove most of what was there before – forests, grasslands, wetlands. Cows, sheep, chickens and pigs are hungry, so the demand for soybeans and other feed shoots up. And cows belch out methane from the fermenting grass in their stomachs. Animal agriculture contributes nearly 15% of the world’s emissions – and cows make up the largest share of that.

While growing and eating plants directly is still the most calorie efficient way to produce food, many people who have grown up eating meat are unlikely to switch to fully vegetarian diets. The taste and texture of animal muscle and fat tissue just can’t be fully replicated by plant proteins and oils.

The mince in your bolognese started as a cow which, in Australia, spent most of its life outdoors, grazing on grass and exposed to the sun.

Cows are much more sensitive to heat than we are, as they can’t get rid of as much heat by sweating. They prefer temperatures below 20℃. During heatwaves, they can suffer heat stress, which can lead to organ failure and death.

Australia has already warmed more than the global average, at 1.4℃. By 2100, if nothing is done, it could be more than 3℃ warmer. Our cows aren’t going to like it.

Cultivated meat is done indoors in temperature-controlled areas. It also allows us to farm vertically, creating a smaller footprint. Beef produced this way requires vastly less land (95% less) and with a fraction of the greenhouse gases (92% less) than traditional beef production, according to a life cycle analysis.

There’s also much less waste. If you want to be able to cook and eat chicken breast and thighs, why not just grow those parts rather than breeding and raising a chicken, complete with digestive tract, brain and feathers? Biopsied muscle cells from chickens can can be grown inside bioreactors, sterile stainless-steel tanks. Another bonus is you don’t need to rely on antibiotics.

Importantly, these muscle and fat cells floating in a broth of plant-based nutrients (called culture medium) promise to be much better at converting food into muscle mass. For every three calories of broth, we could get one calorie of meat in return.

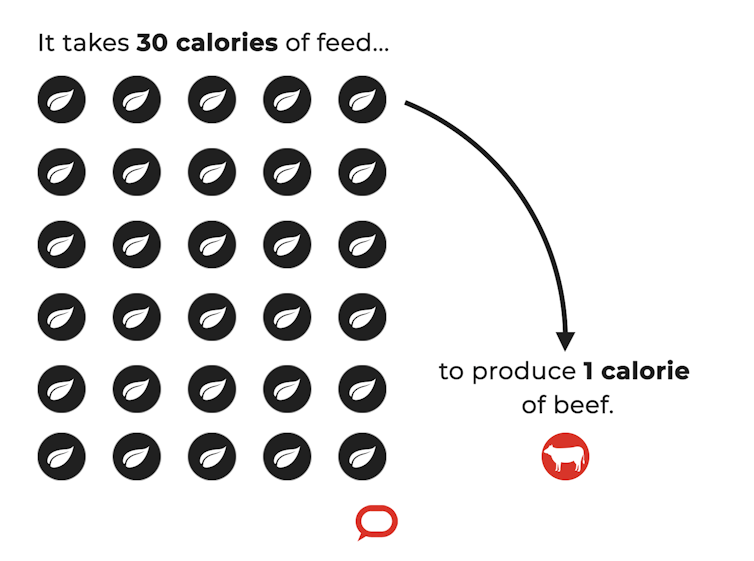

Chickens convert food to meat at an 8:1 ratio. But cows need much more. For every ~30 calories of feed a cow eats, we get 1 calorie of food in return.

Their ceaseless demand for food – and ever-growing herds – are the main driver of the destruction of tropical forests. Two fifths of all tropical deforestation is to make more pastures for cows, with 18% of this deforestation done to plant oilseeds like soybeans, most of which become cattle food.

So why isn’t cultivated meat in supermarkets?

In 2013, the world saw the first ever burger made from cultivated meat. It cost A$512,000. Investment poured in and the cost plunged. By 2017, advocates were predicting cost parity with traditional meat within five years.

It’s 2023 – so where is it? While some products are getting closer, they’re still not cheaper than traditional meat. Sceptics argue the technological barriers are insurmountable.

There’s some merit to this critique. Scale is the hardest step for any new technology. Many cultivated meat companies have succeeded in the laboratory, but none have gone all the way to commercial scale. There are still issues to iron out, such as ensuring bioreactors stay sterile at large scales, and navigating food regulations. Last year’s economic turbulence has also seen private investment drop, though public investment has risen.

Small, high-tech countries like Singapore and Israel are leaders in this area. Both nations are acutely aware of their climate vulnerabilities and dependence on food imports.

Singapore imports 90% of its food, for instance. This is why they’re looking at cultivated meat as well as other alternative proteins. Two years ago, Singapore became the first place in the world where you can actually buy cultivated meat. This didn’t just happen. They invested in talent, streamlined regulations and actively set out to attract companies.

Could Australia follow suit?

Australia has been one of the world’s top three beef exporters for more than 70 years. We’re also a biotech leader. Two decades ago, Australia’s biotech sector was tiny. Now it’s amongst the top five in the world.

Growing cells in culture has been done for decades in biomedical research. What’s new is applying this biotech knowledge to food.

Is it a threat to farmers? Not necessarily. Diversifying into new protein markets – as US beef giants like Cargill are doing – could help Australian farmers and agribusinesses stay competitive. Australian startups like Vow and Magic Valley want to kickstart the local cultivated meat industry. Vow plans to launch its cultivated quail in Singapore.

We’ll need a combination of private and public investment to overcome the remaining technical and financial barriers to scale. Cellular Agriculture Australia has laid out three ways government investment could encourage this sector: develop talent, create cooperative research centres and build flexible biomanufacturing infrastructure for pilot and full-scale plants.

As we face an increasingly uncertain future, it might be a smart move to secure our food supply while protecting ourselves against climate change – and reducing environmental damage.

Bianca Le, Honorary Fellow, The University of Melbourne

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

To stay up-to-date on the latest industry headlines, sign up to Future Alternative’s enewsletter.

Posted on: