Beth Parkin, University of Westminster

Farming animals for food is responsible for around 14.5% of global greenhouse gas emissions. If left unchallenged, the influence of this industry alone would probably make it impossible for the world to meet its target of limiting global warming to 1.5°C.

Reducing meat consumption is one area where small changes in everyone’s behaviour can have a big impact across a country. Animal-based foods need huge amounts of land and energy to make: and they produce twice as many greenhouse gas emissions compared with their plant-based counterparts. If every person in the UK were to switch just one beef or lamb-based meal a week to a plant-based option, the nation would enjoy an 8% reduction in domestic emissions.

The plant-based food sector has been experiencing huge growth recently, with higher quality, more visible meat alternatives on offer and companies such as the plant-based substitute Beyond Meat becoming household names. Yet consumption trends in the UK tell a different story. While there has been a small reduction in the amount of red meat eaten over the last ten years, we are currently eating more poultry than ever before.

Research suggests that for peak personal and planetary health, each of us shouldn’t eat more than 98g of red meat and 203g of poultry per week. That’s around one portion of red meat and two of poultry – or one steak and two chicken sandwiches. For a typical UK adult, that means at least halving their daily meat consumption.

Our research

While it may seem intuitive that increasing the availability of plant-based food will make us eat more of it, very little is known about whether this actually works in practice. I wanted to determine exactly how far meat availability needs to decrease to affect meat eaters’ food choices.

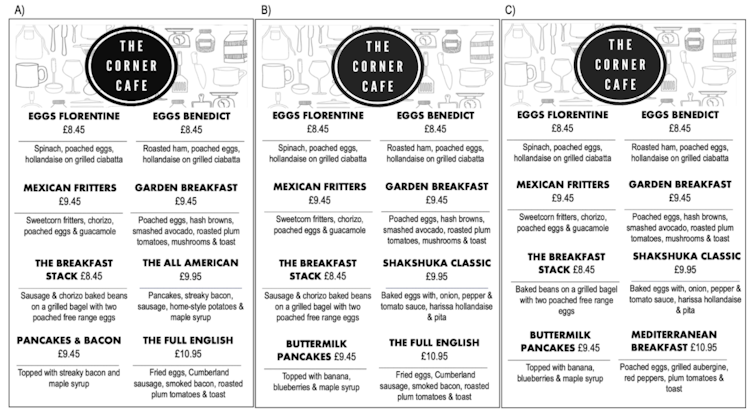

To investigate this, I and my colleague Sophie Attwood presented meat eaters with menus that had different amounts of meat and vegetarian dishes. Menus were composed of either 25% (menu A), 50% (menu B) or 75% vegetarian dishes (menu C), and participants were asked to make hypothetical choices about what dishes they would order.

Our results showed that making vegetarian food more available does significantly encourage sustainable food choices. Participants who usually ate meat only shifted their choice to vegetarian food when these items made up 75% of the menu, but not when menus were equally meat and vegetarian, or when menus were 75% meat. In fact, the likelihood of a participant choosing a vegetarian meal was almost three times greater when the menu was 75% vegetarian compared to when the menu was 50% vegetarian.

Clearly, meat eaters are able to change their eating habits and explore new options. But this tipping point only occurs when ample vegetarian options are present.

While the exact mechanism behind this is unknown, we think that increasing the availability of vegetarian food may implicitly suggest socially acceptable norms for behaviour – or just provide customers with a wider range of options that they might not have previously considered.

This type of intervention is known as “nudging”. It involves modifying the context in which a decision is made, in order to make a certain course of action more appealing. One popular example of a nudge that attempts to steer people away from choosing unhealthy food is reducing the accessibility of chocolate bars and sweets by moving them away from checkout tills in supermarkets.

These interventions have several advantages over other tactics used to change people’s behaviour: they are cheap, easy to put in place across a wide area, and much less difficult than, for example, trying to persuade individuals of the benefits of pro-environment diets. Also, they are less politically sensitive than more dramatic interventions, such as increasing tax on or banning meat products.

Our work highlights the potential that restaurants and cafes have for promoting sustainable eating behaviour among meat eaters. However, the ratio of meat-to-vegetarian dishes currently offered in most dining establishments needs to be reversed, so that vegetarian options vastly exceed the number of meat dishes.

Put simply, if the food service sector is to get serious about tackling the climate crisis, we need more than just one or two additional vegetarian items added to our menus.

Beth Parkin, Senior Lecturer in Cognitive Neuroscience, University of Westminster

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

To stay up-to-date on the latest industry headlines, sign up to Future Alternative’s enewsletter.

Posted on: